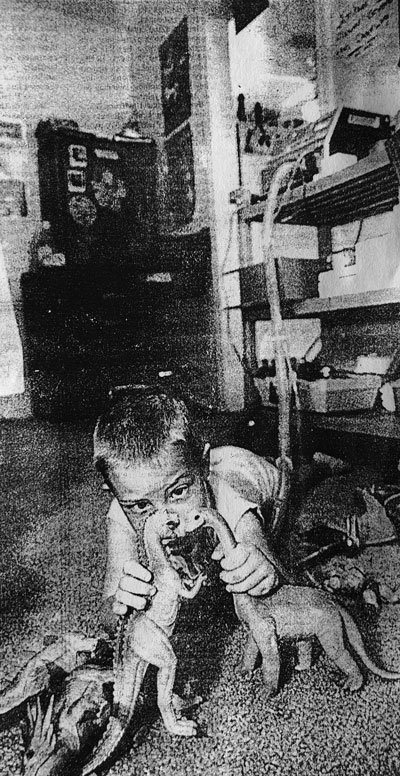

Josh Skinner (1990)

Disclaimer: The following was transcribed from an article in the Capper Foundation Archives published by the Topeka Capital-Journal. The choice of words used at the time this was written may not reflect current Capper Foundation inclusive language and views.

Boy Thrives in Year at Home

by Vicki Griffith Hawver

Coming home was good medicine for Joshua Skinner.

The boy, who was born with a rare illness, had spent all three and a half years of his life at Stormont-Vail Reginal Medical Center. He got to come home–albeit with a ventilator as his nearly constant companion–in July 1989.

A year later, Josh is flourishing. He has gained weight, has been in mostly good health and, perhaps above all, finally has been able to nestle into the love of his 24-hour-a-day family – his parents, Keith and Cathy Skinner; his brother, Travis, 7 ½, and his aunt, Lori Woollums, who lives at his home.

A year later, Josh is flourishing. He has gained weight, has been in mostly good health and, perhaps above all, finally has been able to nestle into the love of his 24-hour-a-day family – his parents, Keith and Cathy Skinner; his brother, Travis, 7 ½, and his aunt, Lori Woollums, who lives at his home.

“Josh is very happy,” Cathy Skinner said simply and smiled as she watched her son mischievously pit dinosaur and He-Man figures against each other. “He’s ornery sometimes too. It’s great to have him home after all the time.”

Josh was born Dec 20, 1985, with Werdnig-Hoffmann’s disease, an infantile muscular disease.

But Josh defies the disease: He surpassed the life expectancy for a child with Werdnig-Hoffman’s more than a year ago.

“We’re taking it one day at a time,” Skinner said. Josh is so healthy now that he only has to see his pediatrician, Dr. Dan Kelly, every six months.

“Dr. Kelly, commented one time that Josh may outlive us all,” Skinner said.

Josh has generally normal intelligence for his age, Skinner said. “He’s a little behind because of his motor skills and his speech pattern,” she said.

He has a tracheotomy in his throat to which the ventilator tube is attached. Because of the tracheotomy, he is not supposed to be able to talk, Skinner said.

But Josh long ago learned to force air around the tracheotomy so he can talk in a raspy voice. He chatters as he plays, and he talks to visitors about the family’s cats.

Because of his illness, he doesn’t walk. But he crawls easily and confidently.

He goes to preschool at the Capper Foundation for Crippled Children three times a week.

He plays with his big brother, Travis, and likes the things Travis likes-dinosaurs, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Batman. The boys are acquiring a taste for Dick Tracy, too.

Josh’s bedroom is in what could serve as a dining area just off of the living room. A big white teddy bear peers out from Josh’s bed and a Batman logo hangs above it.

The ever-present ventilator is near the bed. Even though Josh is tethered to it via the tube, he seems to discount its presence and the limitations if imposes as he frolics on the floor with his toys.

“It’s a way of life for him,” Skinner said. “He’s never known anything different.”

He’s so used to the tube that he’s quick to pop it back in when it comes out, before the ventilator’s warning buzzer goes off.

When Josh goes to school or on outings to the zoo, movies and other fun places, he is seated in a large wheelchair that includes a portable ventilator powered by a battery pack.

The wheelchair is so heavy that it’s difficult to maneuver it into vehicles on the family’s street. The family earlier had asked the city to make a curb cut to help simplify handling of the wheelchair but had been told that was not possible, Skinner said. Edie Snethen, the city’s public works director, said this week that she hadn’t heard of this request but that her staff will look into the matter.

Josh is able to be off all ventilators for three 45-minute periods a day. Skinner takes advantage of that freedom to allow her son to splash in a wading pool. He also gets to go into the pool at Capper once a week.

The family has taken Josh on a trip to visit friends in Fort Riley. They hope to be able to take him on a family vacation next summer to visit Cathy Skinner’s relatives in Iowa.

Josh’s disease is an inherited disorder of the nervous system, according to “The American Medical Association Encyclopedia of Medicine.” A motor-neuron disease, it affects the nerve cells in the spinal cord that control muscle movement.

Marked floppiness and paralysis usually occur during the first few months of an affected baby’s life. The disease also impairs the muscles the control breathing and feeding.

During Josh’s three-plus years at Stormont-Vail, the pediatrics nurses grew to love him; the boy, in fact, became well known by other staff members because he would dash through the halls on a four-wheeled scooter board and a battery-powered motor bike.

Despite nightly family visits to the hospital and the nurses loving attention, being hospitalized for more than three years just couldn’t match being at home.

Josh was physically able to go home long before he did, Skinner said. The problem was that his expensive care could be reimbursed by third-party payers while he was hospitalized, but they couldn’t pay for it if he was at home receiving home-health services-even though home-health care is cheaper.

Finally financial arrangements were worked out. Josh’s home care is paid through a combination of his father’s health insurance and government assistance.

The Skinners have learned to operate Josh’s ventilators and a suction machine. He must have his lungs suctioned throughout the day.

Mid-America Reginal Home Care, a home-health company in the Stormont-Vail corporate family manages his complicated case. The Skinners oversee Josh’s ventilator at home during the day, Capper staff monitors it at the pre-school and a Mid-America nurse watches over Josh each night as he and his parents sleep.

Most of his night care is provided by four rotating nurses, three of whom were Josh’s pediatrics nurses at Stormont-Vail. They moonlight for Mid-America.

The nurses are thrilled that they can continue contact with Josh, said Maggie Clements, one of the three.

“We all got really attached to Josh while he was in the hospital,” Clements said. “He’s a very sweet little boy.”

“He had a lot of mother figures in the hospital, but it’s better for him to have just one, and Cathy does an excellent job. He’s just progressed so much at home. He needed to be home.”

Perhaps even Josh knew that. On that day last July when he knew he would be coming home, Josh woke up at 5a.m., looked at his nurse and said, “Go home now.”