Corey Guliford (2002)

Disclaimer: The following was transcribed from an article in the Capper Foundation Archives published by The Topeka Capital-Journal. The choice of words used at the time this was written may not reflect current Capper Foundation inclusive language and views.

Corey Guliford (2002)

by Paul Eakins

Corey Guliford has been working hard for the past several months learning to get from here to there with his new power wheelchair.

When he isn’t practicing with his wheelchair at Chase Middle School, Corey might be found using a computer to learn to read with special assistive technology or attending classes with his fellow seventh-graders. Corey, a 12-year-old with cerebral palsy, has to work especially hard in school and in life.

On Wednesday, he was recognized for his efforts with the Richard Clark Assistive Technology Award, an honor given by the Capper Foundation to one student each year from Kansas or Missouri. He received the award with his mother, Colletta Guilford, amid a standing ovation during an assembly at the school.

On Wednesday, he was recognized for his efforts with the Richard Clark Assistive Technology Award, an honor given by the Capper Foundation to one student each year from Kansas or Missouri. He received the award with his mother, Colletta Guilford, amid a standing ovation during an assembly at the school.

Although Corey’s progress came from his own hard work and dedication, he wouldn’t have had the opportunity to use his power wheelchair without the help of teachers and students at Chase.

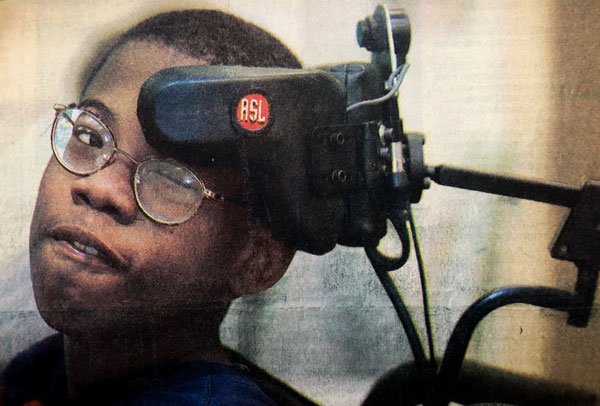

Corey, a friendly, bespectacled student who loves to smile, doesn’t have the strength or mobility in his upper body to operate a regular wheelchair, and even the joystick on a powered wheelchair is difficult for him. So, the school began an effort to collect the more than $5,000 needed for a wheelchair driving system that can be controlled by the user’s head.

Last spring, the money was collected in less than two months. In November, Corey’s new power wheelchair with head array was ready to go.

The head array uses a light beam that senses the position of Corey’s head and relays the commands to the chair’s wheels and motor. When Corey moves his head back against the headrest and light sensor, the chair propels him forward. Leaning his head far enough to the left or right turns the chair in the appropriate direction. Moving his head forward will stop the chair.

But learning to control the chair wasn’t easy, he said. “It was a pretty hard experience for me,” Corey said. “But you know, you learn to get used to it.”

Mary Hayden, a special education teacher at Chase, said the adjustment to the chair has been frustrating for Corey because he has had someone else moving him from place to place for most of his life.

“He had envisioned himself zooming around the world in the beginning, but he may start to get mad at it,” Hayden said. “This will be the first time he’s moving himself through space and time, so it causes him to have to think right, left, back, front, adjust not to hit anybody, to be careful, when to go fast, when to go slow. He’s experiencing a lot of things for the first time in his whole life.”

Now, Corey can drive around corners and through doorways, and he is learning to maneuver in smaller, more cluttered environments.

“It’s helped me think a lot more, and it helps me out in the real world,” Corey said.

Corey continues to practice driving his wheelchair each day with paraprofessional Jimmy Crisp, going to class and even going outside to drive around the block on the sidewalk for about 20 minutes each afternoon.

During the week, the power wheelchair stays at the school in the evenings, but Corey has been taking it home on weekends and will use it over the summer. Improving Corey’s abilities with the chair at school was important before he took it home full time, Hayden said. “It’s such a big change. I have children that when they get a new piece of technology, it takes the family quite a while to adjust to the difference in their home life. That’s normal.”

Hayden began the effort to get Corey’s head array, but she said the work put in by so many others amazed her.

Many organizations and individuals contributed time or money. Through bake sales, car washes, collecting students change and a benefit basketball game between students and staff members. Chase accounted for more than $500 of the money raised. A donation of $2000 by United Cerebral Palsy of Kansas and large donations by other organizations made up the difference.

“It was a real humbling, large group experience,” Hayden said. “It was right, and people could understand that it was right, and they helped.”

Capper Award

The Richard Clark Assistive Technology Award was founded in 1995 and is given to a Kansas or Missouri resident through age 21 who has a disability and uses assistive technology. The Capper Foundation gives the award for outstanding achievement in the use of assistive technology in the areas of communication, mobility, computer access and/or environmental controls.